We're flipping tipping!

Summary

Twenty years ago, there were hardly any electric cars on the roads. Fast forward to today, and we’re seeing them everywhere. The advancement of EV battery technology is a principal reason for this change. This is an example of a tipping point. In this case, a positive one. At least from an emissions reduction standpoint (I won’t go into the possible negative repercussions of mass EV adoption). These tipping points happen all of the time, be it at a small or large scale.

Unfortunately, due to anthropogenic climate change and other factors, we’re toeing the edge of far more dangerous tipping points. Ones in which large-scale ecosystem collapse could occur, or where our livelihoods in the temperate climate of Western Europe could look closer to those in the colder Eastern Europe, undermining our food and water security. I first came across the concept of tipping points when reading Malcolm Gladwell’s excellent book Tipping Points. However, I only came across climate tipping points a couple of months ago. Since then, an important report called the Global Tipping Points Report 2025 has been released. Some may argue that there exists a false urgency in the tipping points community. However, I think it’s better to be safe than sorry. This post touches on some of the key things that I took away from reading this report, and I give my (non-expert) opinion on some of these. My goal is not to scare anyone. It’s to bring to awareness the possibly imminent severity of crossing certain tipping points if we’re to continue with business as usual.

Setting the scene

A double-edged sword

As touched on, tipping points aren’t always negative. They also aren’t unique to ecological systems. Social systems contain them too. As we move into the future, it’s of great importance that we act in a way that keeps us away from the negative ones and pushes us towards the positive ones. We must work together now to trigger positive tipping points – ones that will help rebuild the fabric of society and the ecosystems that we depend upon. For some time now, I’ve begun to understand that systemic change is crucial in addressing the most pressing challenges that we currently face. Individual action can only get us so far. If the system is broken, we have little hope. We must rewire our psychology both at an individual and collective level to get to the root of our problems.

Luckily, we’re already seeing the seeds of systemic change. Take for example the Global South, who are pioneering regenerative agricultural practices and development. We’ve lots to learn from the Global South in the often technocratically minded Global North. Through effective cooperation, we can work towards scaling up technologies, infrastructure, and systems that support positive change across the globe. However, I cannot brush past the deep irony here. These regions pioneering certain positive changes are also the ones most at risk from the effects of climate change – which is primarily driven by the Global North – and, more specifically, crossing certain tipping points. The localised impacts of climate change are already affecting vulnerable small island communities, for example. If this doesn’t sum up climate injustice, then what does? We’re forcing these regions to work overtime to develop transformative, sustainable technologies, but many of them are bearing the burden of our wrongdoing.

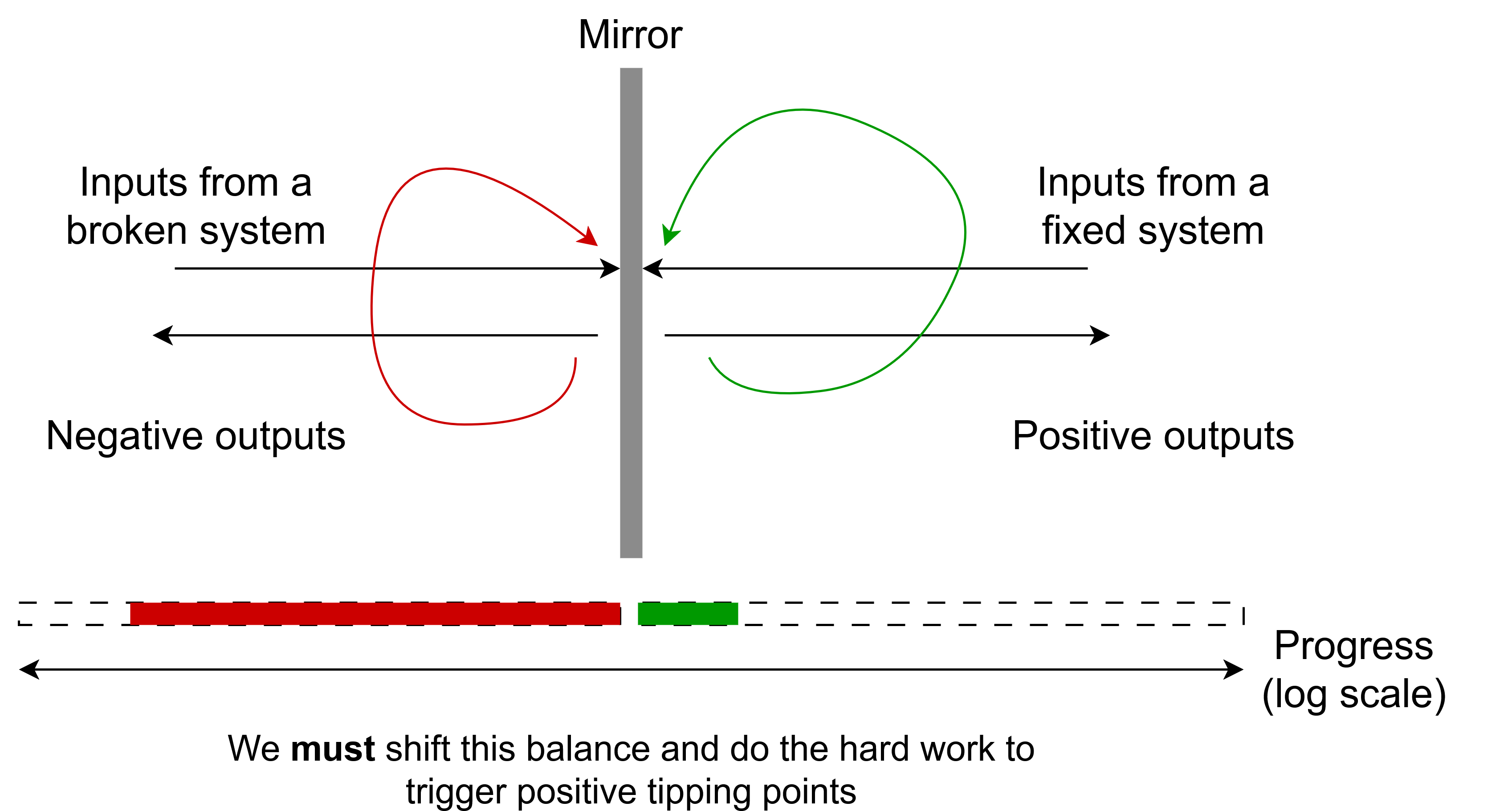

My mirror analogy of positive and negative tipping points/changes.

I digress. What’s apparent to me is that for each negative societal or ecological tipping point, there exists a positive analogue. I like to think of it as a two-sided mirror. I’ve tried to illustrate this in the above diagram. My view is that for every tipping point of danger – that is, a negative one – there exists an opportunity to identify a positive tipping point. I guess this is simple logic – without problems, if everything was perfect, we’d have no context nor reference to know what’s positive and negative. In some sense, awareness of negative tipping points and our approach towards them can be used to our advantage to search for positive ones. Currently, we’re still heavily on the wrong side of the mirror – our inputs are negative and undermine natural processes and systems. Consequently, we’re returned with negative outputs – increasing global temperatures, decreasing soil health, etc. At present, we still have an opportunity to explore more of the other side of the mirror – the side where positive systemic change catalyses positive outcomes, both societally and ecologically. The bars next to the ‘progress’ axis are my attempt to illustrate my view on the current scene. I believe that we’ve pushed the Earth system close to its limits (the red bar inside the dashed bar), where negative tipping points are soon to be triggered. Conversely, I believe that we’ve taken the first steps towards positive transformation (the green bar); however, we have a long way to go (on average) before we can tip positive tipping elements. So why bother switching sides? Especially when I am not a victim of these negative tipping points yet. The reason is simple: if we continue as we are, we’ll cross tipping points that are irreversible (more on this later) – they’ll diminish any light on the right side of the mirror, making it incredibly difficult to recover from the situation. One of these major tipping points has already gone. However, if we take action and face up to the exciting challenge of driving towards positive tipping points, we can simultaneously work to avoid the negative tipping points and start to reap the rewards of our action. We must shift from an egocentric mentality towards a worldcentric view, where we develop awareness and empathy for all living beings and natural systems.

So this is all well and good, but how do we know where to start? The leader of COP30 states that the very point of the conference for him is to relate climate action to people’s lives. Whether or not this ambition was fulfilled is not up to me to say (no agreement on banning fossil fuels…?). However, we must involve people, as we’re the drivers of climate change and positive change. The difficulty arises due to the uncertainty in our predictions of possible tipping point behaviour. When taking a measurement with a metre rule in a physics class at school, you always had to make sure to note down the uncertainty in your measurement. Maybe for a 10 cm long piece of string, your uncertainty would be +/- 0.1 cm (a mm). In this case, the percentage uncertainty is small at 1%. The issue with tipping point estimation at the moment is that there remain large uncertainties around the temperature at which certain tipping elements will tip. Consequently, we’re left in a scenario where the best we can do is provide estimates of low and high temperature limits, saying with near complete certainty that a tipping point will be triggered if we exceed the upper limit.

In my opinion, uncertainty is used as an excuse in many areas related to climate to proceed with business as usual. When presented with a ‘spectrum’ of possibilities, we tend to pick and choose the narrative that best supports continued economic growth. However, of great concern, current policies will probably cause multiple systems to tip. Even worse, these systems interact with one another, with potential cascading effects – most of these being destabilising, where the tipping of one system destabilises and accelerates the tipping of another – that are completely unknown to us.

This risk is existential

To be blunt and truthful – the risk associated with crossing negative tipping points is an existential one. Billions of people across the world could be affected either directly or indirectly. Add to this the risk amplification due to probable increased geopolitical tensions induced by crossing these tipping points too, and we may all be gone due to this, not the tipping of systems directly.

More precisely, this is a human rights issue, and the “Inter-American Court of Human Rights recognises the right of humans to a safe climate”. It’s therefore a legal imperative and obligation to prevent irreversible harm. Something that would be certain if we crossed global tipping points. We must work from both sides to address this challenge. Collective action from civil society must be engendered to help trigger positive tipping points. Policies must be implemented by the people with power now to move away from fossil fuels before it’s too late. We must move away from the ‘us vs government’ mentality towards an ‘us and government’ mentality and acknowledge that this is a social issue as much as it is a technical one. It’s a unique governance challenge and an opportunity to tackle climate injustice and combat hunger, poverty, and wider inequality simultaneously.

Not all tipping elements are equal

So, we might think that it’s a simple challenge to solve: don’t cross negative tipping points, cross positive ones. But in reality, not all tipping elements are the same. That is, the evolution of a system before, during, and after tipping is not a one-size-fits-all.

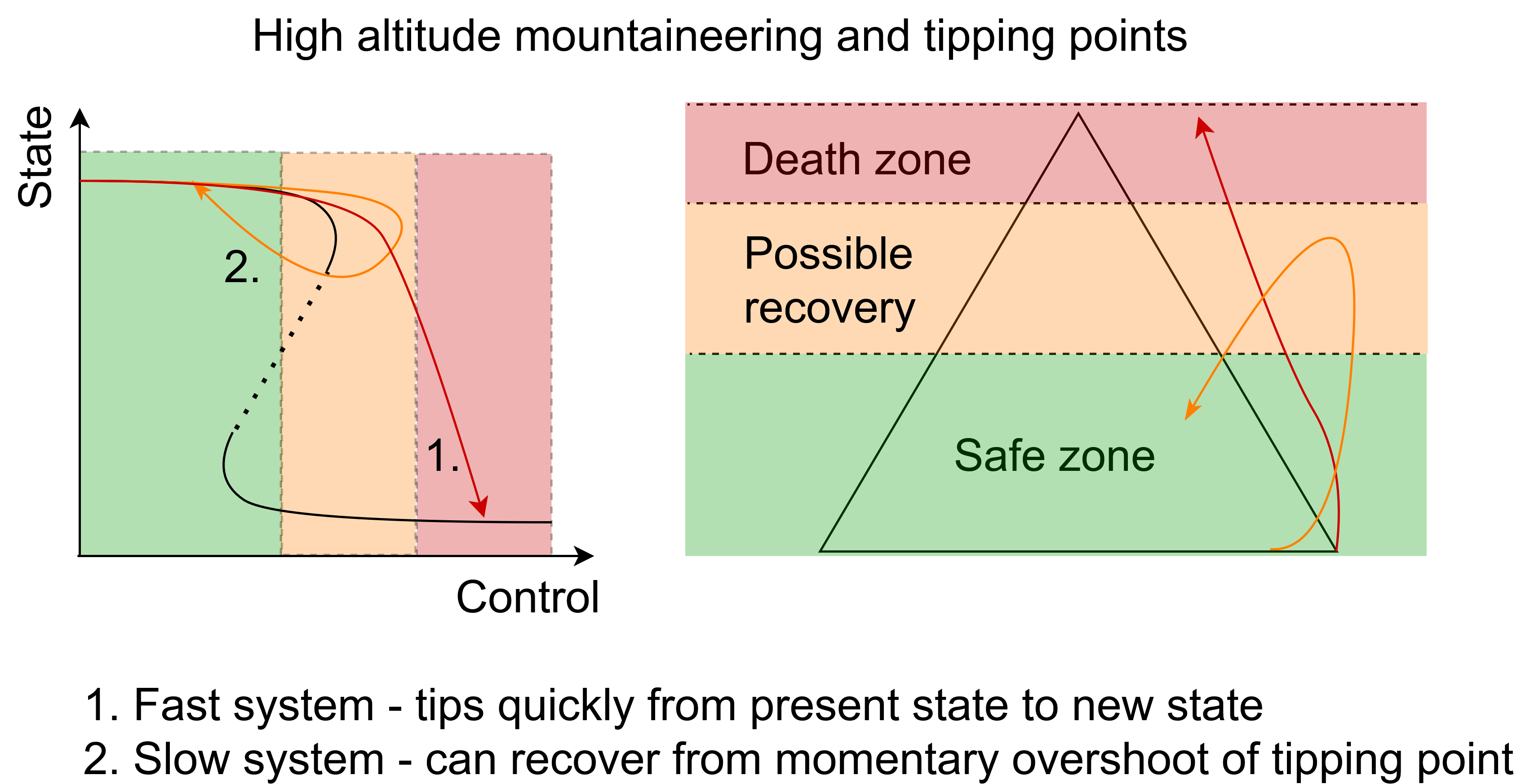

To better understand what tipping means more generally, I’ve tried to use my creativity to create an analogy using high-altitude mountaineering as the analogue. In the diagram below, the ‘chart’ to the left is roughly what tipping of a given system from one state to another looks like. Such systems can be referred to as ‘bistable’, meaning that they can exist in one of two stable equilibrium states. For the layperson, we can think of it simply as a seesaw, where one stable state is where the seesaw is leaning one way, and the other is when it is leaning the other way (it’s more complex than this, but this will do for now). In the diagram, the ‘upper branch’ represents one stable state, and the lower branch represents another. As we crank up our control variable – global temperature, for example – we move along the black ‘line’ in the chart. If we crank our variable up too much, we ‘tip’ from one stable state into the other. This is scenario 1 in the diagram. This can be thought of as someone climbing Everest and doing one push to the top without acclimatising. They’ll end up dying from hypoxia in the death zone, possibly even at some point before. Their new stable state is being dead – the same system, but now the stable state has gone from being alive to dead. Now, the reason not all tipping elements are equal is because this behaviour occurs only in fast tipping systems. If a system tips slower, then there is a region where we can operate in – continuing to crank up our control – where we can recover from a temporary overshoot in our control. This is scenario 2 in the diagram and is similar to high-altitude mountaineering in my head, where we can spend some time at higher altitudes and survive (stay in the alive state) so long as we return to lower altitudes quickly enough. For tipping elements, this means that we could possibly get away with exceeding, let’s say, 1.5 degrees; however, we must limit the time we spend here.

My high-altitude mountaineering analogy for tipping points / changes.

Unfortunately (and fortunately regarding positive tipping points), it’s not quite as simple as looking at one control variable such as global temperature. This is because there are multiple anthropogenic and non-anthropogenic stressors that can increase the likelihood of climate tipping. Moreover, as most elements act to amplify global warming, it could be very difficult to return to lower warming levels (the safe zone in the mountaineer’s case) before it’s too late.

Prioritising ecology over economy

Before I touch on the positive side of tipping points, I’d like to give my opinion on something. The report discusses the interaction of different systems and their feedback on one another. There’s a web of connections that’s ever increasing in complexity – the interaction of energy infrastructure, food security, economic stability, and social cohesion – all domains that will be affected by the crossing of both positive and negative tipping points. Yes, we must work towards a systems-level understanding of the interaction of these different components. However, in my view, we must place ecology and justice at the centre of any decision-making or research that we undertake. For decades, perhaps even centuries, we’ve prioritised the economy over ecology. I think that now is the time to prioritise ecology at the temporary expense of the economy. Otherwise, I can’t imagine a future where extreme economic losses aren’t incurred, be it in the form of shocks or a slow degradation of the currently broken economic model.

So this leads me into finishing on a lighter note – positive tipping points.

Triggering positive tipping points

As touched on, if we’re to create systemic change, we must work towards triggering positive tipping points. They exist everywhere – from improving public transport infrastructure to creating more sustainable, regenerative food systems. It’s essential that we now try to prod government and push for policy change but also work from the bottom up by, for example, demonstrating easily imitable behaviours that can be aggregated at scale, such as active travel.

An example that’s given is the progression of battery storage and heat pump technology. Over the past few years, we’ve gone through somewhat of a tipping point with these technologies, and we’re now seeing their widespread adoption worldwide. However, I am cautious to suggest that technological solutions are the most important component of the transformation that we will have to undergo. This is primarily due to my scepticism regarding how well understood the negative consequences of such technologies are. We don’t want to trigger any unknown tipping elements.

A common way of illustrating technological adoption is through the use of S-curves. As time passes, the initially slow progression of a given technology accelerates rapidly, and we have a period where the technology develops linearly before hitting a point where its development stagnates again. This is great, but I don’t think we should put too much blind faith in technological advancements to save us. We’ve seen the negative effects of our technocracy in the past… Consequently, stringent and correct governance of developing technologies is required, and we must focus on working with, not against, communities to avoid the same mistakes from the past. This means evenly distributing the benefits of rapid decarbonisation – not simply regionally, but globally. This is a big ask, but it’s having the right intention that matters. Otherwise, we’ll continue driving society towards further polarisation, only contributing to accelerated progression towards negative tipping points.

A good example given about the importance of implementing policy to normalise and spread sustainable behaviours is in the food system. The report states that:

Policy and market structures currently incentivise harmful practices. Subsidies and procurement should change towards sustainable production and consumption, thereby supporting sustainably productive landscapes…

This demonstrates the need to work from the top down – through subsidies, incentives, and other support – to facilitate the development and thereafter continued support of sustainable landscapes. Countless times I’ve discussed how, for example, the food system is currently designed with big corporations’ profit in mind. I’m certain that a shift towards health, wellbeing, sustainability, and regeneration being at the centre of the food system would help trigger a huge positive tipping point. Moreover, such change would likely cause many downstream and upstream cascading effects that could rapidly restore nature and biodiversity. For example: more sustainable food -> incentive to grow organic produce -> improved soil health and working environment -> improved biodiversity and quality of life. You get the gist. Effective policy implementation can then be combined with local community action, such as grassroots environmental movements, to kick-start positive feedback loops, eventually leading to positive tipping. I have hope and stubborn optimism that this change is possible soon. In fact, now.

We’re already tipping

Having said that I’d end on a positive note, I felt that I needed to end by stating that we’re already crossing some negative climate tipping points. Warm-water coral reefs are experiencing mass bleaching events, leading to huge mortality rates in these reefs. Even under the most optimistic emissions reduction scenarios, these coral reefs are almost certain to cross their tipping point. This is serious stuff. We must act now to help avoid the possible catastrophic effects of the tipping of warm water coral reefs and other tipping elements such as the AMOC, the Amazon Rainforest and mountain glaciers.

I urge you to start small and do what you can to start taking steps towards positive tipping points, be they societal or ecological ones. We all have the power to help drive for change. It’s just about realising that we have this gift of agency at our disposal.